Which Nursing Action is Appropriate When Advancing the Rate of a Continuous Tube Feeding

Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Gastrointestinal Intubation and Special Nutritional Modalities

A preliminary assessment of the patient who requires a tube feed-ing includes several considerations.

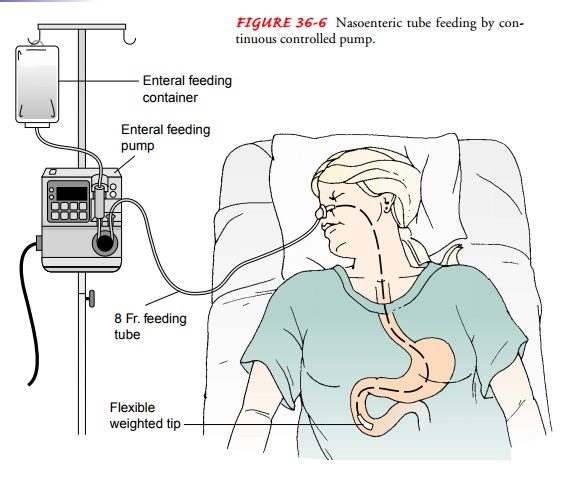

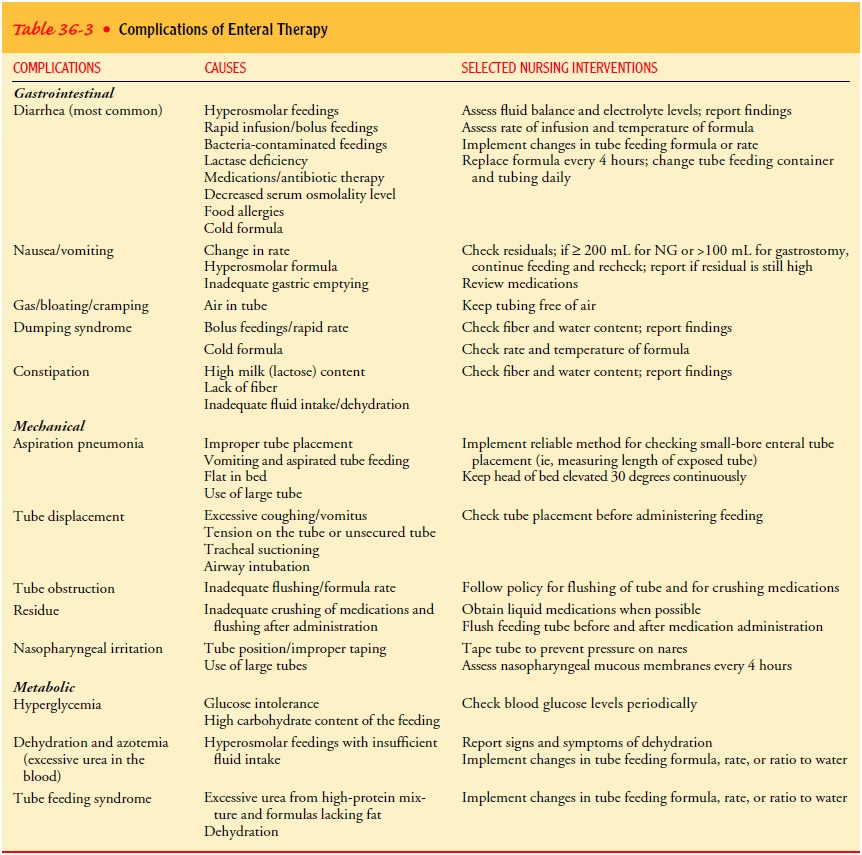

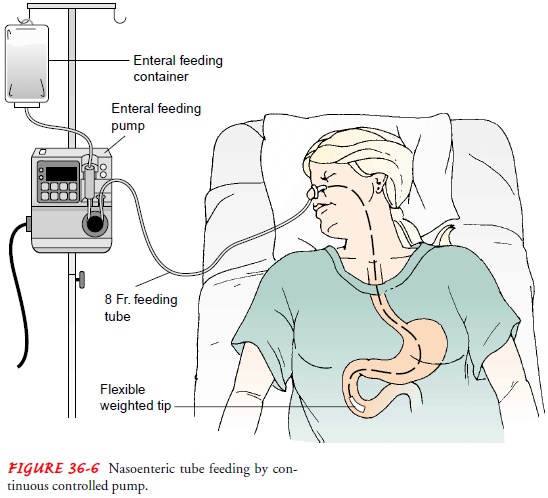

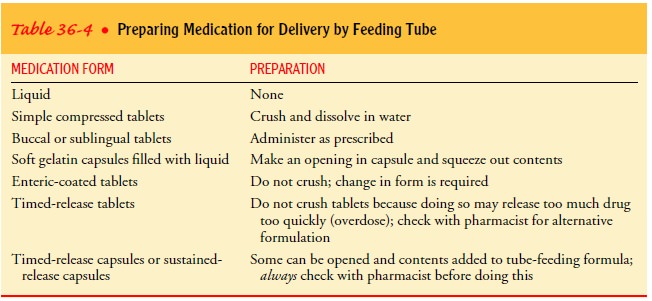

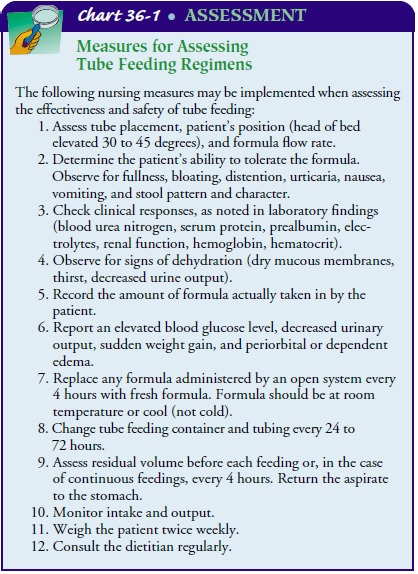

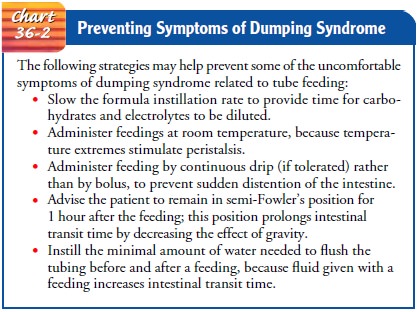

NURSING PROCESS:THE PATIENT RECEIVING A TUBE FEEDING A preliminary assessment of the patient who requires a tube feed-ing includes several considerations, as well as the family's need for information: • What is the patient's nutritional status, as judged by current physical appearance, dietary history, and recent weight loss? • Are there any existing chronic illnesses or factors that will increase metabolic demands on the body (eg, surgical stress, fever)? • What is the patient's hydration status? What are the elec-trolyte levels? • Is the patient's digestive tract functioning? • Are the kidneys functioning normally? • Are fluid requirements (ie, 30 to 40 mL/kg body weight) being met? • What medications and other therapies is the patient re-ceiving that may affect digestive intake and function of the digestive system? • Does the dietary prescription fulfill the patient's needs? In addition, a more elaborate assessment is performed for pa-tients who require extensive nutritional therapy. A team that in-cludes the nurse, physician, and dietitian conducts this assessment. In addition to the history and physical examination (which in-cludes anthropometric measurements), nutritional assessment consists of recording any weight change; determining albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin levels and total lymphocyte count; testing for the delayed hypersensitivity reaction; and evaluating muscle function. Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses may include the following: • Imbalanced nutrition, less than body requirements, related to inadequate intake of nutrients • Risk for diarrhea related to the dumping syndrome or to tube feeding intolerance • Risk for ineffective airway clearance related to aspiration of tube feeding • Risk for deficient fluid volume related to hypertonic dehy-dration • Risk for ineffective coping related to discomfort imposed by the presence of the NG or nasoenteric tube • Risk for ineffective therapeutic regimen management • Deficient knowledge about home tube feeding regimen Complications of NG and nasoenteric tube feeding therapy are classified into three types—GI, mechanical, and metabolic. Table 36-3 lists complications, possible causes, and appropriate interventions. The major goals for the patient may include nutritional balance, normal bowel elimination pattern, reduced risk of aspiration, ad-equate hydration, individual coping, knowledge and skill in self-care, and prevention of complications. The temperature and volume of the feeding, the flow rate, and the total fluid intake are important factors to be considered when tube feedings are administered. The schedule of tube feedings, in-cluding the correct quantity and frequency, is maintained. The nurse must carefully monitor the drip rate and avoid administer-ing fluids too rapidly. Feedings are administered by gravity (drip), bolus, or continu-ous controlled pump (mL/hour or drops/hour). Gravity feedings are placed above the level of the stomach, with the speed of ad-ministration determined by gravity. Bolus feedings are given in large volumes (300 to 400 mL every 4 to 6 hours). Continuous feeding is the preferred method; delivery of the feeding in small amounts over long periods reduces the incidence of aspiration, distention, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Continuous admin-istration rates of about 100 to 150 mL/hour (2400 to 3600 calo-ries/day) are effective in inducing positive nitrogen balance and progressive weight gain without producing abdominal cramps and diarrhea. If the feeding is intermittent, 200 to 350 mL is given in 10 to 15 minutes. Enteral pumps are mechanical devices that control the delivery rate of feeding formula (Fig. 36-6). Pumps allow for a constant flow rate and can infuse a viscous for-mula through a small-diameter feeding tube. These pumps are relatively heavy and must be attached to an IV pole. For home use, there are portable lightweight enteral pumps available that weigh about 4 pounds and are easy to handle. An enteral pump is available with an automatic water flush system. In addition to administering the feeding formula, these pumps provide hourly water flushes that are designed to prevent clogged feeding tubes (Petnicki, 1998). Residual gastric content is measured before each intermittent feeding and every 4 to 8 hours during continuous feedings. (This aspirated fluid is readministered to the patient.) The research findings of McClave et al. (1992) indicated that, if the amount of aspirated gastric content is greater than or equal to 200 mL for NG tubes or if residual volumes are greater than or equal to 100 mL for gastrostomy tubes, tube feeding intolerance should be con-sidered. Tube feedings may be continued with close monitoring of gastric residual volume, radiographic studies, and the patient's physical status. If excessive residual volumes occur twice, the nurse notifies the physician. Maintaining tube function is an ongoing responsibility of the nurse, patient, or primary caregiver. To ensure patency and to de-crease the chance of bacterial growth, crusting, or occlusion of the tube, 20 to 30 mL of water is administered in each of the follow-ing instances: • Before and after each dose of medication and each tube feeding • After checking for gastric residuals and gastric pH • Every 4 to 6 hours with continuous feedings • If the tube feeding is discontinued for any reason When different types of medications are administered, each type is given separately, using a bolus method that is compatible with the medication's preparation (Table 36-4). The tube is flushed with 20 to 30 mL of water after each dose. If a liquid form of a medication is not available and the medication can be crushed, it must first be reduced to a fine powder or the tube will become clogged. Devices are available (eg, Handicrush Irrigation Syringe by Nestle) that crush and dissolve tablets with water (Fig. 36-7). Medications are not mixed with each other or with the feeding formula. When small-bore feeding tubes for continuous infusion are irrigated after medication administration, a 30-mL or larger syringe is used, because the pressure generated by smaller syringes could rupture the tube. Tube feeding formula is delivered to patients by either an open or a closed system. The open system comes in cans or as a powder and may be mixed with water. The feeding container (which is hung on a pole) and the tubing used with the open system are changed—usually every 24 to 72 hours. To avoid bacterial cont-amination, the amount of feeding formula in the bag should never exceed what is expected to be infused in 4 hours. Closed delivery systems use a prefilled, sterile container that is spiked with enteral tubing. The bag holding the feeding formula for the closed system can be hung safely for 24 to 48 hours. The tube-feeding regimen must be assessed frequently to eval-uate its effectiveness and avoid complications (Chart 36-1). Patients receiving NG or nasoenteric tube feedings commonly have diarrhea (watery stools occurring three or more times in hours). Pasty, unformed stool is expected with enteral ther-apy, because many formulas have little or no residue. The dump-ing syndrome also leads to diarrhea, but to confirm dumping syndrome as the cause of diarrhea other possible causes must be ruled out, among them the following: • Zinc deficiency—Adding 15 mg of zinc to the tube feeding every 24 hours is recommended to maintain a normal serum level of 50 to 150 fg/dL (7.65 to 22.95 fmol/L) • Contaminated formula • Malnutrition—A decrease in the intestinal absorptive area resulting from malnutrition can cause diarrhea • Medication therapy—Antibiotics, such as clindamycin (Cleocin) and lincomycin (Lincocin); antiarrhythmics, such as quinidine and propranolol (Inderal); and aminophylline, theophylline, and digitalis have been found to increase the frequency of diarrhea in some patients The dumping syndrome results from rapid distention of the jejunum when hypertonic solutions are administered quickly (over 10 to 20 minutes). Foods high in carbohydrates and elec-trolytes draw extracellular fluid from the vascular system into the jejunum so that dilution and absorption can occur. Measures for managing the GI symptoms (diarrhea, nausea) associated with the dumping syndrome are presented in Chart 36-2. Aspiration pneumonia occurs when stomach contents or enteral feedings are regurgitated and aspirated, or when an NG tube is improperly positioned and feedings are instilled into the pharynx or the trachea. Nasoenteric tubes, especially those that provide for gastric and esophageal or duodenal decompression, have helped decrease the frequency of regurgitation and aspiration. To prevent aspiration, the nurse must establish the correct tube feeding placement before every feeding, each time medica-tions are administered, and once every shift if the tube feeding is continuous. Feedings and medications should always be given with the patient in the proper position to prevent regurgitation. To reduce the risk of reflux and pulmonary aspiration, the semi-Fowler's position is necessary for an NG feeding, with the pa-tient's head elevated at least 30 to 45 degrees. This position is maintained at least 1 hour after completion of an intermittent tube feeding and is maintained at all times for patients receiving continuous tube feedings. Another prevention strategy is to mon-itor residual volumes (Edwards & Metheny, 2000). If aspiration is suspected, the feeding is stopped immediately, the pharynx and trachea are suctioned, and the patient is placed on the right side with the head of the bed down. The physician is notified immediately. The nurse carefully monitors hydration because, in many cases, the patient cannot communicate the need for water. Water (at least 2 L/day) is given every 4 to 6 hours and after feedings to pre-vent hypertonic dehydration. At the beginning of administration, the feeding is diluted to at least half-strength and not more than 50 to 100 mL is given at a time, or 40 to 60 mL/hour is given in continuous drip administration. This gradual administration helps the patient to develop tolerance, especially for hyperosmo-lar solutions. Key nursing interventions include observing for signs of dehydration (dry mucous membranes, thirst, decreased urine output); administering water routinely and as needed; and monitoring intake, output, and fluid balance (24-hour intake ver-sus output). The psychosocial goal of nursing care is to support and encour-age the patient to accept physical changes and to convey hope that daily progressive improvement is possible. If the patient is having difficulty adjusting to the treatment, the nurse intervenes by encouraging self-care (eg, recording daily weight and intake and output), within the parameters of the patient's activity level. In addition, the nurse reinforces an optimistic approach by iden-tifying signs and symptoms that indicate progress (daily weight gain, electrolyte balance, absence of nausea and diarrhea). Patients who require long-term tube feedings in the home care setting have conditions such as obstruction of the upper GI tract, malabsorption syndrome, surgery of the GI tract or of the head or neck region, or decreased level of consciousness. For a patient to be considered for tube feeding at home, the following criteria must be met: The patient must be medically stable and must have successfully completed a tube feeding trial (tolerated 70% of feeding). In addition, the patient must be capable of self-care or have a caregiver who is willing to assume the responsibility, and the patient or caregiver must have access to supplies and interest in learning how to administer tube feedings at home. Preparation of the patient for home administration of enteral feedings begins while the patient is still hospitalized. Ideally, the nurse teaches while administering the feedings so that the patient can observe the mechanics of the procedure, participate in the procedure, ask questions, and express any concerns. Before dis-charge, the nurse provides information about the equipment needed, formula purchase and storage, and administration of the feedings (frequency, quantity, rate of instillation). Family members who will be active in the patient's home care are encouraged to participate in all teaching sessions. Available printed information about the equipment, the formula, and the procedure is reviewed. The nurse encourages the patient and care-giver to learn to use the equipment with the supervision of the nurse. Arrangements are made for the caregiver to obtain the equipment and formula and have it ready for use before the pa-tient's discharge. Referral to a home care agency is important so that a nurse can arrange to be present to supervise and provide support during the first feeding at home. Further visits will depend on the skill and comfort of the patient or caregiver in administering the feedings. During all visits, the nurse monitors the patient's physical status (weight, vital signs, activity level) and the ability of the patient and family to administer the tube feedings correctly. In addition, the nurse assesses for any complications (dumping syndrome, nausea or vomiting, weight loss, lethargy, confusion, excessive thirst). The patient or caregiver is encouraged to keep a diary to record times and amounts of feedings and any symptoms that occur. The nurse reviews the diary with the patient and caregiver during home visits. Expected patient outcomes may include the following: 1) Attains or maintains nutritional balance a. Has a positive nitrogen balance b. Maintains laboratory values within normal limits (ie, blood urea nitrogen, hemoglobin, hematocrit, prealbu-min, serum protein) c. Attains or maintains hydration of body tissue d. Attains or maintains desired body weight 2) Is free of episodes of diarrhea a. Has fewer than three watery stools a day b. Does not have a bowel movement after a bolus feeding c. States that there is no intestinal cramping d. Has normal bowel sounds 3) Avoids aspiration a. Lungs are clear to auscultation b. Exhibits normal heart rate and respirations 4) Attains or maintains hydration of body tissue a. Has a balanced intake and output every 24 hours b. Does not have dry skin or dry mucous membranes 5) Copes effectively with tube feeding regimen 6) Demonstrates skill in managing tube feeding regimen 7) Experiences no complications a. Has no GI disturbances b. Tube remains intact and patent for duration of therapy c. Maintains metabolic balance within normal limits Assessment

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Planning and Goals

Nursing Interventions

MAINTAINING FEEDING EQUIPMENT AND NUTRITIONAL BALANCE

PROVIDING MEDICATIONS BY TUBE

MAINTAINING FEEDING REGIMENS AND DELIVERY SYSTEMS

MAINTAINING NORMAL BOWEL ELIMINATION PATTERN

REDUCING THE RISK OF ASPIRATION

MAINTAINING ADEQUATE HYDRATION

PROMOTING COPING ABILITY

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

Continuing Care

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Study Material, Lecturing Notes, Assignment, Reference, Wiki description explanation, brief detail

Medical Surgical Nursing: Gastrointestinal Intubation and Special Nutritional Modalities : Nursing Process: The Patient Receiving a Tube Feeding |

Source: https://www.brainkart.com/article/Nursing-Process--The-Patient-Receiving-a-Tube-Feeding_32067/

0 Response to "Which Nursing Action is Appropriate When Advancing the Rate of a Continuous Tube Feeding"

Postar um comentário